Cetaceans

Assessment of progress towards the achievement of Good Environmental Status for cetacean biodiversity.

Extent to which Good Environmental Status has been achieved

The extent to which Good Environmental Status has been achieved for cetaceans remains uncertain. The status of coastal bottlenose dolphin and minke whale are consistent with the achievement of Good Environmental Status in the Greater North Sea, but unknown/uncertain elsewhere.

It is unknown if Good Environmental Status has been achieved for other species.

How progress has been assessed

In the UK Marine Strategy Part One (HM Government, 2012), the UK set out the following “Characteristics of Good Environmental Status ” for biodiversity:

“At the scale of the Marine Strategy Framework Directive Sub-Regions, and in line with prevailing conditions, the loss of biodiversity has been halted and, where practicable, restoration is underway:

The abundance, distribution, extent, and condition of species and habitats in UK waters are in line with prevailing environmental conditions as defined by specific targets for species and habitats.

Marine ecosystems and their constituent species and habitats are not significantly impacted by human activities such that the specific structures and functions for their long-term maintenance exist for the foreseeable future.

Habitats and species identified as requiring protection under existing national or international agreements are conserved effectively through appropriate national or regional mechanisms."

The extent that Good Environmental Status, as articulated in the criteria for biodiversity in the Commission Decision 2010/447/EU (European Commission, 2010), had been achieved was assessed using targets set out for cetaceans in the UK Marine Strategy Part One (HM Government, 2012). The status of each cetacean species was assessed against a target for Population Size. A separate assessment was carried out under the target for Population Condition of the numbers of cetaceans killed through bycatch in fisheries. Indicators relevant to the targets which used data collected by monitoring programmes in the UK and by neighbouring countries were then agreed, in cooperation with OSPAR. With the exception of discrete groups of coastal bottlenose dolphin, the cetaceans found in UK waters are part of much larger populations whose range extends beyond UK waters. The appropriate scale for the assessment of Good Environmental Status for cetaceans is the North East Atlantic, which encompasses the Greater North Sea and Celtic Seas Sub-Regions and wider Atlantic to the west of the UK and Ireland. The status of each species was assessed separately. To achieve Good Environmental Status, the status of all species assessed would need to be consistent with its achievement as articulated for biodiversity (see Figure 1).

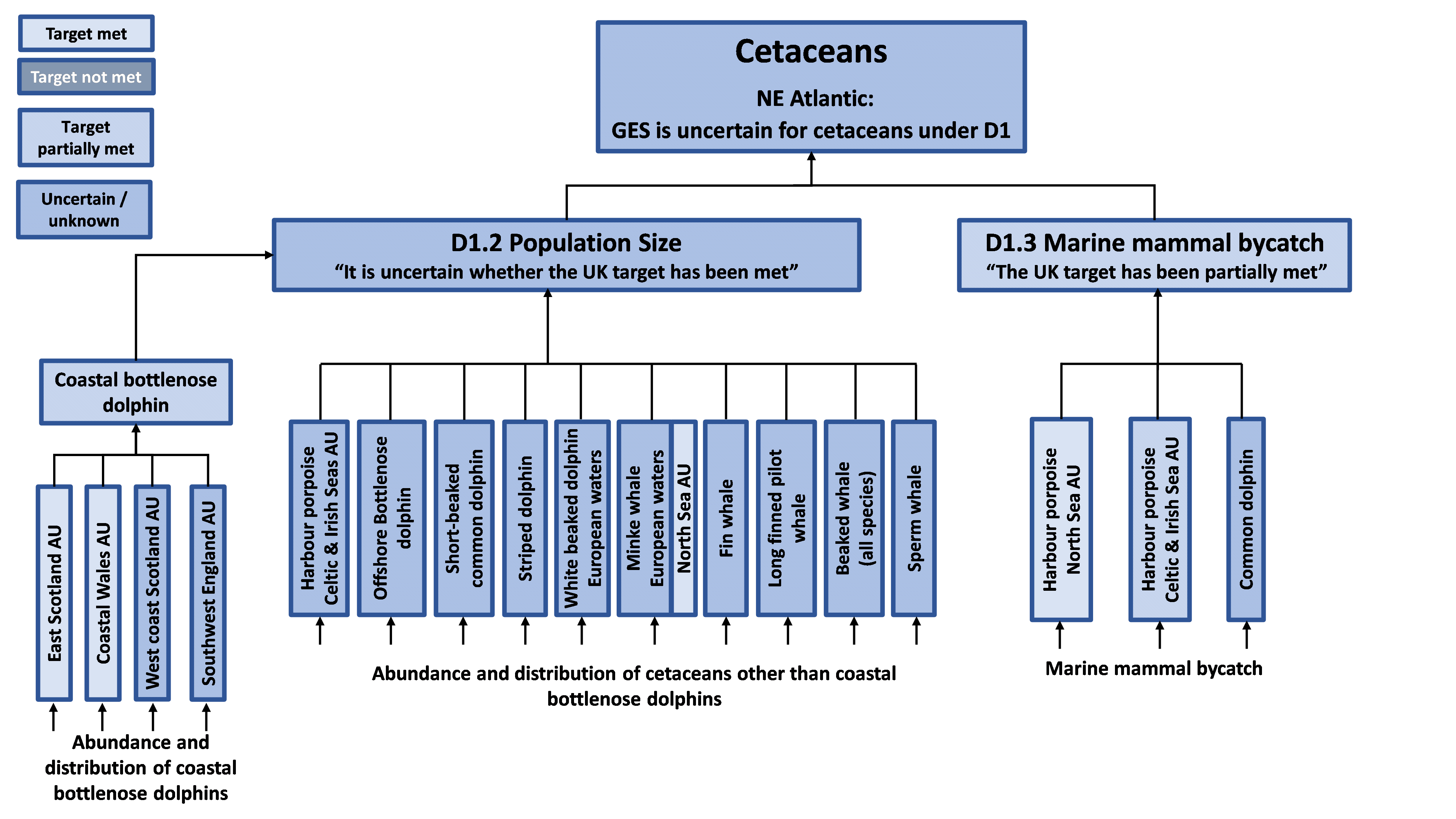

Figure 1: Schematic showing how indicators and targets were integrated to assess progress towards Good Environmental Status (GES) for cetaceans in the North East (NE) Atlantic. AU: Assessment Unit. D1 indicates the Marine Strategy Framework Directive Descriptor 1: “Biological diversity is maintained.” (European Commission, 2008), with D1.2 D1.3 referring to the targets defined in the UK Marine Strategy Part One (HM Government, 2012).

Progress since 2012

Since 2012, cetacean population estimates have been updated by an international survey. Sufficient data are now available to determine that numbers of minke whale have remained stable in the Greater North Sea over the last 20 years. For most other species the most recent estimates of abundance were similar to or larger than previous estimates made in comparable areas.

Outstanding issues

There are still insufficient data for most species to assess trends in the Greater North Sea or more widely at the North East Atlantic scale. For most species, abundance has been estimated only once prior to this assessment. Bycatch in fisheries is an ongoing pressure, with harbour porpoise bycatch likely exceeding the precautionary threshold in the Celtic Seas.

Achievement of targets and indicators used to assess progress

Assessment results are summarized in Table 1. The targets, set out in the UK Marine Strategy Part One (HM Government, 2012) are:

Population size: “in all of the indicators monitored, there should be no statistically significant decrease in abundance of cetaceans caused by human activities.”

Population condition: “mortality of cetaceans due to fishing bycatch is sufficiently low so as not to inhibit population targets being met.”

Table 1. Summary of assessment results and achievement of targets for cetaceans. N.A. indicates not applicable.

|

Target |

Harbour porpoise |

White- beaked dolphin |

Minke whale |

Common dolphin |

other species considered |

Inshore bottlenose dolphin |

|

|

Population size |

North Sea trend |

Unknown/ Uncertain |

Unknown/ Uncertain |

Stable |

N.A. |

Insufficient data |

Stable in East coast Scotland |

|

Celtic Seas trend |

Insufficient data. |

Insufficient data. |

Insufficient data |

Insufficient data |

Insufficient data |

Unknown/Uncertain in West coast Scotland |

|

|

Stable in Coastal Wales |

|||||||

|

Unknown/Uncertain in SW England |

|||||||

|

Population condition (assessed using numbers of animals killed annually by fishing bycatch) |

North Sea |

Bycatch mortality below precautionary threshold of 1% of population estimate |

N.A. |

N.A. |

N.A. |

N.A. |

N.A. |

|

Celtic Sea trend |

By catch mortality below threshold of 1.7% of population estimate, but above precautionary threshold of 1% |

N.A. |

N.A. |

Insufficient data |

N.A. |

N.A. |

|

|

Overall Species Status |

NE Atlantic |

Unknown/Uncertain |

|||||

Further information

Assessment of the target on cetacean population size

Since 2012, population estimates of cetaceans in the North East Atlantic have been updated by an international survey. Sufficient data are now available to assess trends in numbers of harbour porpoise, white-beaked dolphin, and minke whale. In the Greater North Sea, the UK abundance target of no significant decline was met for minke whale. The abundance of harbour porpoise and white-beaked dolphin appeared to be stable, but uncertainty in the data meant a decline could not be ruled out. The spatial range of harbour porpoise and minke whale in the Greater North Sea has remained the same, but the centre of their distribution has shifted southwards. There are still insufficient data over time to assess if populations of these three species have changed at the North East Atlantic scale, as abundance in North East Atlantic has been estimated only once prior to this assessment.

In UK waters, there are around 700 coastal bottlenose dolphins living in four groups. The UK target of ‘no statistically significant decrease in abundance’ was met in the Greater North Sea and for the largest group in the Celtic Seas. No assessment has been possible for the two smaller Celtic Seas groups.

For other species, abundance has been estimated only once prior to this assessment, so it was not possible to determine trends at the sub-regional or North East Atlantic scale. The most recent estimates of abundance in the Greater North Sea were similar to or larger than previous estimates made for most species

Evidence to support the assessment of cetacean population size

The supporting evidence for this target evaluation and the extent the relevant criteria in the Commission Decision 2010/447/EU (1.2, European Commission, 2010) and in the Commission Decision 207/848/EU (D1C2, European Commission, 2017) have been achieved comes from the assessment of two indicators, detailed in the following sections.

Abundance and distribution of coastal bottlenose dolphins

In European waters, bottlenose dolphins consist of a large, wide-ranging offshore population and much smaller coastal groups. This indicator assessment has been undertaken as part of the OSPAR Intermediate Assessment (OSPAR Commission, 2017a). In UK waters, there are around 700 coastal bottlenose dolphins living in four groups. One of these occurs in the Greater North Sea Sub-Region (East Coast Scotland), which incorporates the Moray Firth Special Area of Conservation (SAC) and consisted of 170 individuals in 2014. The other three occur in the Celtic Seas sub-region. The largest UK coastal bottlenose dolphin group inhabits the coastal waters off west Wales (included in the Cardigan Bay and the Pen Llyn a’r Sarna Special Area of Conservation) and held 222 individuals in 2015. Elsewhere in the Celtic Seas, there are thought to be around 45 bottlenose dolphins off the west coast of Scotland and approximately 100 individuals around the south-west coast in England.

The UK target of ‘no statistically significant decrease in abundance’ was considered to be achieved if there was no decrease of greater than 5% over a ten-year period. This assessment required at least four abundance estimates from different years within a ten-year period. The numbers of dolphins within the East Coast Scotland and Coastal Wales groups have been monitored frequently for more than ten years, through a combination of photo-identification and line-transect survey techniques which enable changes to be tracked. There were insufficient data to assess trends in the size of the groups in south-west England and the west of Scotland.

The UK target of ‘no statistically significant decrease in abundance’ was met in the Greater North Sea, where numbers in the only coastal group, in East Coast Scotland, have been stable since the Initial Assessment (HM Government, 2012), following a steady increase during the 2000s. Their range has extended south from the Moray Firth to as far as St Andrews Bay in Fife. Off the east coast of Scotland numbers remained stable until 2000 and thereafter appear to have increased. In the Celtic Seas, there was ‘no statistically significant decrease in abundance’ in the largest group, inhabiting the coastal waters of Wales. Numbers of bottlenose dolphin have been stable there since the Initial Assessment (HM Government, 2012) and since monitoring began. Elsewhere in the Celtic Seas, trends in abundance of bottlenose dolphins off the west coast of Scotland and south-west England were unknown due to insufficient monitoring data.

Abundance and distribution of cetaceans other than coastal bottlenose dolphins

Cetaceans have huge geographic ranges and to understand their abundance and distribution properly it is important to include data from waters, beyond those of the UK. This assessment is taken from the OSPAR Intermediate Assessment (OSPAR Commission, 2017). The OSPAR assessment used data from the third Small Cetaceans in European Atlantic waters and the North Sea survey (SCANS-III), which was conducted in 2016. Irish waters were not included in SCANS-III. In the absence of data from Irish waters, an assessment of the Celtic Seas Sub-Region was not possible. An assessment of only the UK portion of the Celtic Seas could be misleading because cetaceans are very mobile and wide-ranging. Therefore, this UK assessment is currently restricted to the Greater North Sea and uses data from the UK and other European countries.

The target of ‘no statistically significant decrease in abundance’ was met if, over a ten-year period, the abundance of a species increased, or remained stable, or did not decline by 5% or more. SCANS-III yielded the most recent population abundance estimates for nine species that regularly occur in UK waters and a grouping of beaked-whale species. However, at least three abundance estimates are required to determine a trend and to assess the UK target with some degree of confidence. This was possible for minke whale in the Greater North Sea only. The assessment used data on minke whale abundance collected between 1989 and 2016 by a combination of systematic large-scale surveys in 1994, 2005, and 2016 and additional Norwegian data. These data were sufficient, over a 27-year period, to detect the equivalent of a decline of > 5% over ten-years and assess against the UK target. The UK target for population size was met for minke whale in the Greater North Sea, where their abundance has been stable since 1989. This assessment was made with only medium confidence because an assessment of this species should ideally be based on data from across their range in the European Atlantic.

There were three abundance estimates for harbour porpoise and white-beaked dolphins during 1994, 2005, and 2016 in the Greater North Sea. But the power to detect trends from these data was relatively low: over the 22-year time frame, approximately 33% of the harbour porpoise population and 68% of the white-beaked dolphin population would need to disappear before we could detect a decline from these three surveys. While the abundance of harbour porpoise and white-beaked dolphin appeared to be stable, uncertainty in the data meant a decline could not be ruled out. Therefore, the UK target could not be assessed with confidence for harbour porpoise and white-beaked dolphin.

Two abundance estimates were available for a further six species: common dolphin, striped dolphin, bottlenose dolphin, fin whale, sperm whale and long-finned pilot whale, and for beaked whales as a group. An assessment of the trend in abundance was therefore not possible for these species. The data do show that abundance estimates in 2016 were similar to or larger than previous estimates made in comparable areas, suggesting with very low confidence that these species are not declining.

Assessment of cetacean population condition i.e. bycatch mortality

The target has been met in the North Sea, where harbour porpoise bycatch is estimated to be below the precautionary threshold of 1%. The assessment is inconclusive in the Celtic Seas because harbour porpoise bycatch is likely below the threshold of 1.7% of the best population estimate, but it is currently above the precautionary threshold of 1%. While monitoring of the UK fishing fleet is good, there is low confidence in the bycatch estimates due to incomplete monitoring of bycatch across all fleets impacting the populations.

Evidence to support the assessment of cetacean bycatch mortality

The supporting evidence for this target evaluation and the extent the relevant criteria in the Commission Decision 2010/447/EU (1.3, European Commission, 2010) and in the Commission Decision 207/848/EU (D1C3, European Commission, 2017) have been achieved comes from the assessment of the indicator: Harbour Porpoise Bycatch.

The main direct cause of mortality of cetaceans in the northeast Atlantic is being caught and entangled in fishing nets. Harbour porpoise and short-beaked common dolphin are the most commonly caught species in the northeast Atlantic. This assessment focuses on bycatch of harbour porpoise only because the data available on short-beaked common dolphin were insufficient to construct robust estimates of bycatch at an appropriate European scale.

This UK assessment is based on that used by OSPAR for its Intermediate Assessment (OSPAR Commission, 2017c), which uses the latest advice provided by the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES, 2015). The UK assessment focuses on two of the internationally agreed assessment units for harbour porpoise, which contain UK waters and sufficient data on bycatch: the North Sea (covering most of the Greater North Sea Sub-Region), and the Celtic and Irish Seas (including southern half of the Celtic Seas sub-region and inshore waters of the French part of the Bay of Biscay sub-region). Bycatch has not been monitored or assessed recently in the West of Scotland Assessment Units where it is thought to be very low due to regulations on fishing practices.

Bycatch estimates are derived from estimates of annual fishing effort and counts of bycaught harbour porpoises. Cetacean bycatch is recorded by observers on commercial fishing vessels, as part of the UK Protected Species Bycatch Monitoring Scheme. ICES have advised caution with regards to their interpretation because many caveats apply to the range of their bycatch estimates, due to the unreliability of fishing effort data and the lack of appropriate monitoring in some fleets.

The UK target was assessed by comparing estimates of annual total bycatch against limits agreed by the Agreement on the Conservation of Small Cetaceans of the Baltic and North Seas (ASCOBANS): ‘total anthropogenic removal’ of harbour porpoises (mortality resulting from all pressures caused by human activities) should not exceed more than 1.7% of the best available estimate of abundance (ASCOBANS, 2000); and to achieve this, bycatch should ideally be less than 1% of the best available abundance estimate and ultimately, be reduced to zero (ASCOBANS, 2006). For this assessment OSPAR used both thresholds. The best population estimate for the Greater North Sea of 345,400 harbour porpoise was taken from the SCANS-III survey in 2016. In the Celtic and Irish Seas Assessment Unit, the best estimate of 107,300 harbour porpoise was taken from the SCANS-II survey in 2005 because the SCANS-III data do not include counts from Irish waters.

Despite uncertainties in the bycatch estimates, the target is likely to have been met in the Greater North Sea: annual bycatch was estimated to be between 0.36 and 0.58% of the best population estimate. In the Celtic Seas, the assessment against the UK target was uncertain: the annual bycatch estimate was between 1.06 and 1.37% of the best population estimate, which is below the Agreement on the Conservation of Small Cetaceans of the Baltic and North Seas threshold of 1.7% for ‘total anthropogenic removal’ but exceeds the precautionary threshold of 1% for bycatch mortality. The confidence in these bycatch estimates is low, and the estimates should be treated with caution due to incomplete monitoring and known biases in the data. The current bycatch estimates are derived from observing only 0.28% of the fishing effort for the fishing gear types classified as ‘nets’. The higher the observer coverage, the greater the reliability of bycatch estimates.

Moving forward

We will aim to determine trends in abundance of cetacean species and the impact of human pressures, such as bycatch and noise disturbance, at a North East Atlantic scale to better assess progress against the UK targets.

We will consider increasing the frequency of our SCANS surveys to improve our confidence in our abundance assessments for more species and make better use of citizen science observations.

We will develop a UK cetacean bycatch strategy.

The assessment of abundance for wide-ranging, highly mobile cetacean species requires data collected by equally wide-ranging, internationally coordinated surveys. The most recent of these was SCANS-III data in 2016. Three precise abundance estimates over at least 10 years, are required to reliably assess trends against the UK targets. Currently, sufficient data exists for only three species to be assessed against the UK targets and only within the Greater North Sea. The next step will be to update abundance estimates in the Celtic Seas by incorporating data from a recent survey of Irish waters (when available) with those from UK and French waters surveyed by SCANS III. This will provide more robust assessments of cetacean abundance in European Atlantic waters and provide an updated abundance estimate for harbour porpoise in the Celtic Seas. This will enable a more accurate assessment in the Celtic Seas of harbour porpoise bycatch, as proportion of the latest abundance estimate, which is currently based on the 2005 SCANS II estimate. Future SCANS type surveys will provide additional estimates which will allow trends in abundance to be assessed for more species.

Two of the four groups of coastal bottlenose dolphins that exist in UK waters are well monitored with assessments based on reliable data. However, such data were lacking to accurately assess the status of the other two groups. The next step will be to collate available data in order to quantitatively assess the status of the coastal bottlenose dolphin residents in Southwest England. In waters around the west coast of Scotland, the resident groups are small and difficult to survey using conventional methods. Alternative methods would need to be developed before the size of this group can be determined accurately.

Robust data on population sizes and trends are also required to indicate with confidence if there is a cause-effect relationship between human activities and abundance and distribution. Determining the impact of human pressures at an appropriate scale is key to assessing progress against the UK target.

One such impact has been assessed here – the extent of bycatch mortality in harbour porpoises. The best available bycatch estimates used in the assessment were provided by ICES. However, confidence in future assessments would be enhanced by more accurate estimates of bycatch rate and of fishing effort across all relevant fleets.

Measures to protect cetaceans are set out in the UK Marine Strategy Part Three (HM Government, 2015). These include the monitoring of incidental capture and killing of cetaceans and to ensure that it does not have a significant negative impact on cetacean population size using conservation measures. European Commission Regulations also require the monitoring of bycatch and the use of acoustic deterrents (‘pingers’) in identified fisheries on vessels of ≥ 12m (European Commission, 2004). It is anticipated that this will continue.

The initiation of projects such as the Collaborative Oceanography and Monitoring for Protected Species (COMPASS) will help build an understanding of how cetaceans use an area of sea and how they may be impacted by or respond to pressure from human activities. The COMPASS project has been recently initiated and will build cross-border capacity for effective monitoring and management of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) through the establishment of a network of oceanographic and acoustic moorings across the regional seas of the Republic of Ireland, Northern Ireland and West Scotland. This network of buoys will enable the effective tracking, modelling and monitoring of aquatic life and the oceanographic processes which influence them. The variety of habitats that the array covers will create a highly informative and varied data set. This will be used to explore the importance of underwater noise in influencing the quality of the marine environment for marine mammals.

References

ASCOBANS (2000) ‘Incidental Take of Small Cetaceans’. Resolution, 28 July 2000, document number UNEP/ASCOBANS/Resolution 3.3 (viewed on 26 November 2018)

European Commisssion (2004) ‘Council Regulation (EC) No 812/2004 of 26.4.2004 laying down measures concerning incidental catches of cetaceans in fisheries and amending Regulation (EC) No 88/98’ Official Journal of the European Union L150, 30.4.2004, p. 12–31O (viewed on 13 December 2019)

European Commission (2008) ‘Directive 2008/56/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 June 2008 establishing a framework for community action in the field of marine environmental policy (Marine Strategy Framework Directive)’ Official Journal of the European Union L164, 25.6.2008, pages 19-40 (viewed 21 September 2018)

European Commission (2010) ‘Commission Decision of 1 September 2010 on criteria and methodological standards on Good Environmental Status of marine waters’ (notified under document C (2010) 5956) (Text with EEA Relevance) (2010/477/EU). Official Journal of the European Union L232, 2.9.2010, pages 14-24 (viewed on 5 July 2018)

European Commission (2017) ‘Laying down criteria and methodological standards on good environmental status of marine waters and specifications and standardised methods for monitoring and assessment’ Commission Decision (EU) 2017/848 of 17 May 2017, repealing Decision 2010/477/EU. Official Journal of the European Union L 125, 18.5.2017, pages 43-74 (viewed on 5 July 2018)

HM Government (2012) ‘Marine Strategy Part One: UK Initial Assessment and Good Environmental Status’ (viewed on 5 July 2018)

HM Government (2015) ‘Marine Strategy Part Three: UK Programme of Measures’ (viewed on 5 July 2018)

ICES (2015) ‘Bycatch of small cetaceans and other marine animals – Review of national reports under Council Regulation (EC) No. 812/2004 and other published documents’ ICES Advice 2015, Book 1, 1.6.1.1; Advice Northeast Atlantic and adjacent seas Published 15 April 2015 (viewed on 21 February 2019).