Marine Protected Areas: moving from designating our ecologically coherent Marine Protected Area to strategically managing MPAs in the UK

MPAs are one of the most important tools we have for protecting the wide range of important and sensitive habitats and species within UK waters. You can explore our network of MPAs using the MPA Mapper tool – developed and hosted by the Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC). The mapper displays MPA boundaries in all UK and Crown Dependency waters, and protected feature information for sites within UK offshore waters.

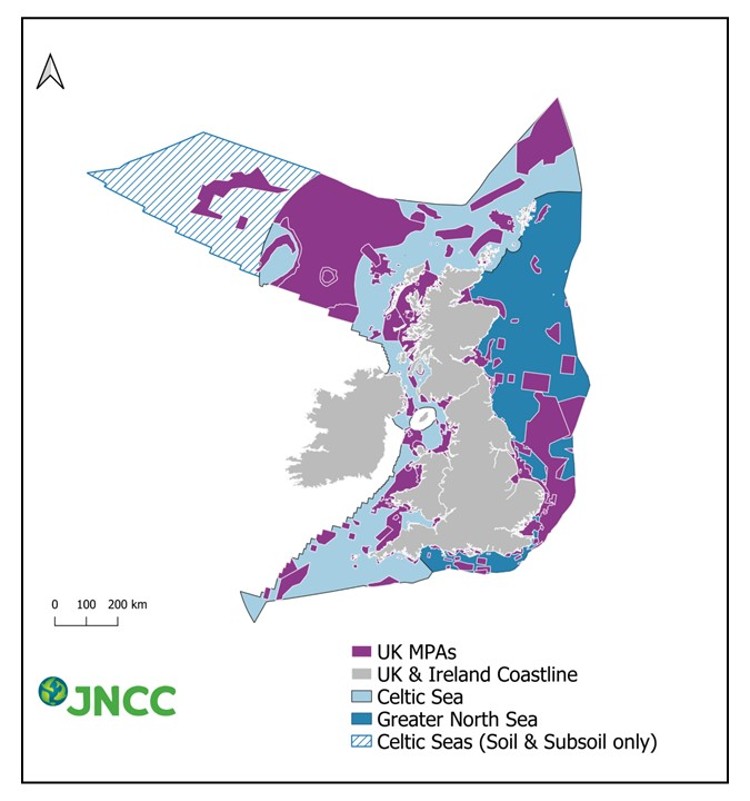

Figure 1: Map showing the location of Marine Protected Areas in UK waters generated by the UK’s MPA Mapper Tool. The mapper, hosted by the Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC), displays MPA boundaries in all UK and Crown Dependency waters, and protected feature information for sites within UK offshore waters. It provides a clear and consistent evidence base to support stakeholder engagement and management of the MPA network.

Progress with developing the UK MPA network

We have continually increased our network of MPAs from 217 sites covering 8% of UK waters in 2012, to 314 designated MPAs protecting 24% of UK waters in 2018. As of May 2024, the UK has designated 377 MPAs, covering 38% of UK waters in total (UK Marine Protected Area network statistics).

Each devolved government approaches the designation of MPAs differently. Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs, the Welsh Government, the Scottish Government and the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs Northern Ireland have recently reported on progress on the MPA network.

In England

We have established a comprehensive network of 181 MPAs (and three Highly Protected Marine Areas – see later note) covering 40% of English waters and set a legally binding target that requires at least 70% of protected features in MPAs to be in a favourable condition by the end of December 2042 with the remainder in recovering condition. We are now focused on the effective management of these sites, which will continue to play an essential role in achieving GES for our seas. The UK government has been increasing protections within MPAs in line with our environmental targets and obligations. To that end, new byelaws and other protections have been put in place in recent times. We are also undertaking a review of the MPA network in England with the aim of future-proofing the network, for example in terms of climate change adaptation and mitigation.

Marine Management Organisation (MMO) byelaws to protect four offshore marine protected areas

Under new powers under the Fisheries Act, the UK established new measures that will prohibit fishing activities in MPAs where there is evidence that they harm wildlife or damage habitats. Following formal consultation between February and March 2021, the MMO created four bylaws that bring management measures on fishing within these four MPAs in English waters:

-

Dogger Bank Special Area of Conservation

-

Inner Dowsing, Race Bank and North Ridge Special Area of Conservation

-

South Dorset Marine Conservation Zone

-

The Canyons Marine Conservation Zone

Under these byelaws, bottom trawls, dredges, demersal seines, and semi-pelagic trawls - collectively known as bottom towed gear - cannot be used over certain areas. Two of the sites also prohibit the use of certain static gear such as pots, nets, or lines over particularly sensitive areas.

These first four MPAs were selected as a priority to preserve their vibrant and productive undersea ecosystems. They include the Dogger Bank Special Area of Conservation, which has the largest shallow sandbank in British waters and supports commercial fish species such as cod and plaice, as well as sand eels that provide an important food source for kittiwakes, puffins and porpoises. They also include the Canyons Marine Conservation Zone which protects rare and highly sensitive deep-water corals.

MPA Bottom Towed Fishing Gear Byelaw 2023

An additional byelaw was made by the MMO in 2023, confirmed by Secretary of State on 1 February 2024 and will come into force on 22 March 2024. The purpose of the byelaw is to protect marine fauna and habitats, including rock, reef and associated biological communities, from the impacts of bottom towed fishing gear.

The byelaw covers specified areas in the following 13 marine protected areas:

-

Cape Bank Marine Conservation Zone;

-

East of Haig Fras Marine Conservation Zone;

-

Farnes East Marine Conservation Zone;

-

Foreland Marine Conservation Zone;

-

Goodwin Sands Marine Conservation Zone;

-

Haig Fras Special Area of Conservation;

-

Haisborough, Hammond and Winterton Special Area of Conservation;

-

Hartland Point to Tintagel Marine Conservation Zone;

-

Land’s End and Cape Bank Special Area of Conservation;

-

North Norfolk Sandbanks and Saturn Reef Special Area of Conservation;

-

Offshore Brighton Marine Conservation Zone;

-

South of Celtic Deep Marine Conservation Zone; and

-

Wight-Barfleur Reef Special Area of Conservation

Highly Protected Marine Areas

Defra designated the first three HPMAs in English waters in Summer 2023, following formal consultation. The three designated HPMAs are Allonby Bay (inshore in the Irish Sea), Dolphin Head (offshore in the Eastern English Channel), and Northeast of Farnes Deep (offshore in the Northern North Sea).

HPMAs are areas of the sea that allow high levels of protection by taking a whole site approach. This means the protected feature of a HPMA is the entire marine ecosystem and includes all species and habitats and associated ecosystem processes within the site boundary.

The conservation objective of a HPMA is to achieve full recovery of the marine ecosystem within the site boundary to a natural state and prevent further degradation and damage.

HPMAs cover approximately 0.4% of English waters and complement the existing MPA network (which covers 40% of English waters).

Management measures for the designated HPMAs will be introduced as necessary.

In Scotland

The MPA network covers 37% of Scottish waters and is comprised of 233 sites designated for nature conservation purposes. Work is currently underway to develop and implement management measures for fishing activity for those MPAs where they are required and are not already in place.

In Wales

Wales has 139 Marine Protected Areas, covering 69% of inshore waters and 50% of all Welsh waters. There are several types of MPAs used in Wales, which offer different levels of protection. As part of the MPA network completion programme, Welsh Government are proposing to designate further MCZs to address shortfalls previously identified. 6 areas of search have been identified in Wales focusing on benthic features.

Northern Ireland

The inshore MPA network currently consists of 48 protected areas, accounting for 38% of the inshore region. The 2024 DAERA Environmental Statistics Report stated that 87% of marine habitat features and 71% of marine mammal features were in favourable status. Northern Ireland’s MPA strategy is regularly reviewed to maximise co-benefits that a well-managed MPA network can provide.