Invasive mammal presence on island seabird colonies

The invasive mammal indicator assesses whether current management measures (including biosecurity) are reducing the risk of invasive mammals impacting vulnerable seabird colonies on protected islands. The target of improvement was met as 34 of the 42 assessed colonies had improved biosecurity measures, and none had deteriorated. Although the target was met, continued funding support will be crucial for sustained protection.

Background

UK target on bird population condition: Invasive mammals

This indicator assesses progress against the following target, which is set in the UK Marine Strategy Part One (DEFRA, 2019a): “At the scale of the UK Marine Strategy sub-regions, the risks to island seabird colonies from non-native mammals are reduced.”

Key pressures and impacts

Seabirds breeding in the UK and elsewhere in the North-East Atlantic experienced declines in abundance and productivity over the last two decades. The invasion of seabird colonies on offshore islands by invasive mammalian predators is one of the important factors contributing to declines of ground-nesting seabirds. In the UK these predators consist of both invasive non-native species such as brown rats, cats, and American mink and also native mainland species that are considered invasive on offshore islands like the hedgehog and fox that have been introduced by humans. Predation of eggs and young birds can cause reductions in breeding success and can lead to the desertion of whole colonies. In the UK, especially the burrow-nesting petrels, terns and puffins are impacted.

Puffins and other burrow-nesting seabirds are especially susceptible to predation from invasive non-native mammals. (Photo credit: Daisy Burnell).

Measures taken to address the impacts

The UK Marine Strategy Part Three (DEFRA, 2019b) states that future implementation of a UK-wide programme of quarantine (also referred to as ‘biosecurity’) against invasive non-native mammalian predators from island seabird colonies and the strategically targeted removal of mammals from some islands will increase our confidence in meeting the above target.

Further information

CBD Target on invasive mammals

The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) formulates a related target (Target 6): “Eliminate, minimize, reduce and or mitigate the impacts of invasive alien species on biodiversity and ecosystem services by identifying and managing pathways of the introduction of alien species, preventing the introduction and establishment of priority invasive alien species, reducing the rates of introduction and establishment of other known or potential invasive alien species by at least 50 percent by 2030, and eradicating or controlling invasive alien species. Especially in priority sites, such as islands”.

The risks to island seabird colonies from invasive predatory mammals

Predation of ground-nesting marine birds, their eggs and chicks by mammals can have impacts at a population scale. The main strategy adopted by seabirds to cope with mammalian predation is avoidance. They tend to nest on cliffs, offshore islands or remote beaches where predators are scarce or absent (Birkhead and Furness, 1985). The introduction of mammalian predators to places where they would not naturally occur without human assistance has had catastrophic impacts on bird populations around the world (see for example: Courchamp and others, 2003; Russell and Clout, 2005; Towns and others, 2006; Jones and others, 2008).

In the UK, Stanbury and others (2017) identified 9,688 distinct islands around the coast of the UK. The vast majority of these are very small; only 506 of them are larger than 10 hectares. Many of these islands have ground-nesting birds that can breed successfully in the absence of predatory mammals. Some of these islands are home to the largest seabird colonies in Europe. However, some islands do have invasive predatory mammals (see Table 1 for species list). The most widespread species on islands are the American mink (Mustela vison) and brown rat (Rattus norvegicus), which occur on 23 % and 21 % of islands (>10 hectares), respectively (Stanbury and others, 2017). Both species are non-native to the UK.

Brown rats are thought to have originated on the steppes of central Asia and spread, possibly naturally, to eastern Europe in the early eighteenth century. Brown rats were first reported arriving in England on ships around 1728 to 1729 (GB Non-Native Species Secretariat, 2022).

The American mink escaped from fur farms following the expansion of the industry in the UK during the 1950s (Dunstone, 1993). They have since colonised almost all of mainland Britain and some of the larger Scottish islands including Skye, Lewis and Harris (see data and maps for Neovison vison in the National Biodiversity Atlas (National Biodiversity Network (NBN) Trust, 2023)). American mink are adept swimmers and can easily reach seabird colonies on inshore islands, where they cause complete breeding failures, adult mortality, and eventually site abandonment. Along the west coast of Scotland, mink predation within the last 10 to 30 years has led to the redistribution and decline in numbers of common and Arctic terns, common and black-headed gulls and black guillemots (Craik, 1997; Craik, 1998; Mitchell and others, 2004).

Brown rats are capable swimmers, able to swim at least 1 km and can also be accidentally introduced on to islands by boats. On islands where rats have been introduced, they can have strong impacts, such as the local extinction of puffins on Ailsa Craig (pre-rat eradication in 1991) and of Manx Shearwaters on Canna. Some species, such as European and Leach’s storm-petrels, are only found breeding on islands that are free of rats (Mitchell and others, 2004). There are numerous examples of seabird species returning to breed on islands following the eradication of rats, for example, Manx shearwaters on Lundy (Lock, 2006).

However, on most islands where rats are present for extended periods of time, their impact is not as obvious. On islands where seabirds and rats co-exist, impacts are evidenced by the location and abundance of nesting seabirds. For example, black guillemots nesting on islands with rats on Orkney and both rats and stoats in Shetland, appeared to mainly nest in crevices high off the ground and on cliffs that are inaccessible to the rats and stoats, rather than in the boulder beaches that they use as nest sites on islands that have no rats or stoats (Ewins and Tasker, 1985). This could suggest the presence of rats and stoats is supressing or restricting the distribution of black guillemots on these islands. Since the study by Ewins and Tasker (1985), stoats have also arrived on Orkney, however their impact on black guillemot populations is not yet known (Fraser and others, 2015). Mitchell and Ratcliffe (2007) found that throughout the UK there were significantly more puffins breeding on islands without rats, compared to islands of a similar size that have rats.

Table 1 lists species of predatory mammals that are of a high risk to ground-nesting marine birds. In contrast to rats and mink, other species of invasive predatory mammals appear to have a much more limited distribution on islands and therefore have a more localised impact on seabirds. In addition to non-native brown rats and American mink, native species can be introduced to islands that they would not naturally get to by swimming. In such cases, these native species are considered invasive. The most widespread invasive native species on UK islands is the hedgehog (Table 1).

Table 1: Species of predatory mammals present on islands in the UK. All species are considered a high risk to ground-nesting birds (Stanbury and others, 2017).

|

Mammal species |

Status in the UK |

% of islands (>10 ha) in UK with confirmed or probable presence* |

|

Brown rat (aka Norway rat) Rattus norvegicus |

Non-native |

21% |

|

Black rat (aka ship/roof rat) R. rattus |

Non-native |

2% |

|

American mink Neovison vison |

Non-native |

23% |

|

Ferret Mustela furo |

Feral |

4% |

|

Stoat Mustela ermina |

Native |

4% |

|

Weasel Mustela nivalis |

Native |

1% |

|

European badger Meles meles |

Native |

1% |

|

Hedgehog Erinaceus europaeus |

Native |

12% |

|

Red Fox Vulpes vulpes |

Native |

2% |

|

Cat Felis catus |

Feral / free-roaming domestic pet |

17% |

Assessment method

Assessment of UK target

The risk to breeding seabird populations from mammalian predation on offshore island Special Protection Areas (SPAs) has been successfully reduced compared to former assessments, therefore meeting the UK target for this indicator.

There were 42 UK offshore Island SPAs which were part of this assessment. All SPAs in the assessment were designated under the Birds Directive (European Commission, 2009) because of the national or international importance of their breeding seabird populations, and all are on islands.

At each of the 42 sites, a risk assessment was carried out to determine if the risk from invasive predatory mammals had been minimised by effective biosecurity. The results of the risk assessment were categorised as follows:

-

‘Yes’: the potential risk (without any biosecurity) had been reduced to a low actual risk by having in place (or planned) ‘sufficient’ biosecurity measures including, quarantine procedures, invasive monitoring scheme and rapid response.

-

‘Partially’: the potential risk had been reduced to a lower actual risk, but not all the biosecurity measures were considered ‘sufficient.’

-

‘No’: the potential risk had NOT been reduced to a lower actual risk and biosecurity measures were absent or ‘below standard.’

To assess whether the indicator target to reduce the risk of invasion by mammalian predators is met, it is determined if there are more colonies in the category of ‘sufficient biosecurity measures’ and the category of ‘partially sufficient biosecurity measures’ than in the last assessment.

Defining an ‘island SPA’

The 42 island SPAs, which were part of the assessment, included a total of 723 islands. Only island SPAs designated wholly or primarily for their breeding seabird interest features have been included. Small islands that are part of a bigger mainland SPA have mostly been excluded, such as Steep Holm and Havergate Island. For the Ynys Feurig, Cemlyn Bay and the Skerries SPA, only the Skerries, which are fully offshore islands, were assessed for biosecurity. Island SPAs were defined as being entirely distinct from the mainland at low tide. Offshore islands permanently surrounded by the sea are less likely to be invaded by mammals than tidal islands that are connected to the mainland by a land-bridge at low tide. Mammals can potentially get to tidal islands during each low tide, occurring twice daily, hence biosecurity measures would be so intensive that they are often not financially or logistically viable. The task would also require a permanent baiting regime - which can have negative environmental consequences in the long-term e.g. secondary poisoning on non-target species, rodenticide in the environment etc. Tidal islands were therefore excluded from this assessment.

Risk assessment approach

The assessment of the actual risk for an SPA to be impacted by invasive mammals is laid out in the flowchart in Figure 1. The majority of the scores of individual steps for the previous assessment were taken from interviews of site managers conducted by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds as part of the Shiant Isles Seabird Recovery Project (Thomas and others, 2016). Additional information was used to supplement the results of these interviews. Since the last assessment the Biosecurity for LIFE project has been working to set up biosecurity plans for all the 42 island SPAs, these plans were used to inform this assessment with respect to quarantine measures, surveillance and rapid response preparedness.

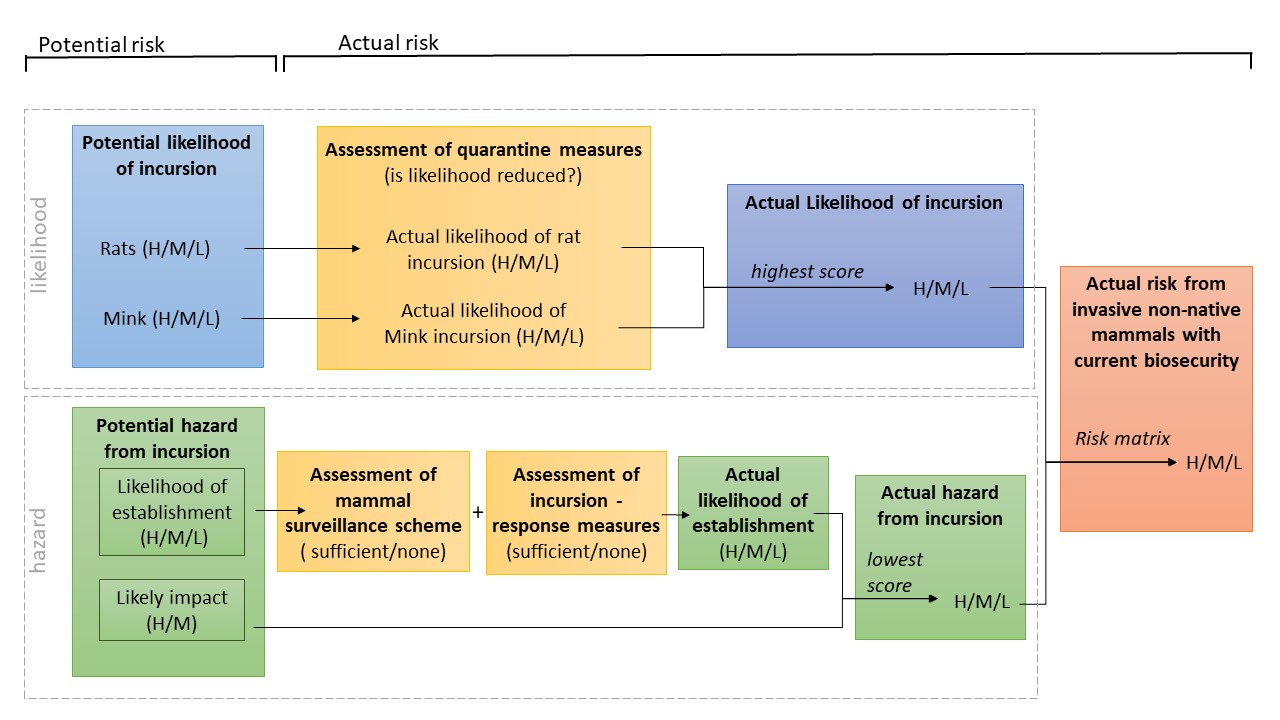

First, the potential likelihood of incursion (without biosecurity) from rats and mink was assessed (low, medium or high, Figure 1) for each SPA. Similarly, the potential hazard was defined for each SPA by determination of the likelihood of the establishment of invasive mammalian predator populations on an island (without biosecurity, as low, medium or high) and the likely impact of invasive mammalian predators on the seabird population (medium or high). For more details on the calculation of the potential risk, see section on ‘Assessing potential risk’.

Following this, the assessment of the potential risk was modified by assessments of biosecurity measures to define the actual risk (Figure 1). Quarantine procedures were considered to affect the likelihood of incursion, and mammal surveillance schemes and incursion response measures were considered to affect the likelihood of establishment. For more details on the calculation of the actual risk see section on ‘Assessing the actual risk’.

The overall actual risk for the SPA was calculated as the product of the actual likelihood of the incursion and the actual hazard from incursion (see risk matrix in Table 2).

Figure 1: Risk assessment framework for assessing whether potential risk from invasive mammalian predators has been reduced to a lower ‘actual risk’ by current biosecurity measures at each site.

Figure 1: Risk assessment framework for assessing whether potential risk from invasive mammalian predators has been reduced to a lower ‘actual risk’ by current biosecurity measures at each site.

Table 2. Risk Matrix used to assess the actual risk to an island seabird population from invasion by invasive mammalian predators.

|

|

|

Likelihood of invasion |

||

|

|

L |

M |

H |

|

|

Hazard associated with invasion |

H |

Medium |

High |

High |

|

M |

Medium |

Medium |

High |

|

|

L |

Low |

Medium |

Medium |

|

The presence or absence of invasive predatory mammals (see species list in Table 1) was determined at all 42 SPAs. On the 29 island SPAs that do not have invasive predatory mammals, the assessment looked at whether biosecurity measures were in place and how effective they are at minimising the risk of these mammals arriving and becoming established, following the entire process as outlined above.

On the 13 island SPAs where invasive predatory mammals are currently present, this assessment focused on whether any biosecurity was in place to prevent further incursion by other species and only the second part of the process, the assessment of the actual risk, was assessed. This is important, since the invasion by new species may impact further on the resident bird communities. Sufficient biosecurity measures will also be important in ensuring the success of future eradication schemes.

Assessing potential risk

Potential risk of invasion by rats or mink was assessed only for sites that are not currently invaded by high-impact mammalian predators. First, the likelihood of incursion on the island was considered. The potential likelihood of incursion by rats and mink was scored separately for each mammalian predator as ‘high,’ ‘medium’ or ‘low.’ The score was dependant on the pathway of introduction, be it natural, such as swimming or human-assisted – usually accidentally by boats visiting an island. The likelihood was assessed by considering the following:

-

Human-assisted introductions: site managers were asked to provide information on the current levels of boat traffic to the island and the nature of the traffic – including types of vessels used and the purposes of visits. Assumptions were made that islands with resident populations would have higher risks of human-assisted pathways than those that were uninhabited. Ratcliffe and others (2009) found no rat-free islands in the UK that were inhabited by more than 100 people and considered islands with a human population less than 10 to be of low risk of invasion, islands with 11 to 50 people being medium risk and over 51 to be high risk.

-

Natural introductions: distances to neighbouring islands containing invasive species, and distance to the mainland determines how likely invasive species could get to the island by swimming there. Brown rats can swim for at least 1 km in open, temperate seas (Russell and Clout, 2005) and occasionally 2 km and possibly 4 km (Thomas and others, 2017). However, Ratcliffe and others (2009) found that many UK islands are rat-free despite being less than 1 km from the mainland, possibly due to strong currents in the channels separating the islands from the mainland. They found that a swimming distance of 300 m fitted better with the observed distribution of rats on offshore islands in the UK. American Mink are much stronger swimmers than rats and can reach islands within 2 km of shore along the west coast of Scotland (Ratcliffe and others, 2009).

Then the risk, based on the vulnerability or potential damage invasive mammalian predators would cause following arrival, was estimated and scored as ‘high,’ ‘medium’ or ‘low’ by considering the following:

-

The likely impact of invasion on resident seabird species – this was scored as ‘High’ for all sites included in this assessment because they are all protected for their important colonies of breeding seabirds, which would certainly be impacted if the site was invaded by a high-impact mammalian predator.

-

The likelihood of establishment of a breeding population of rats or mink following an incursion. This is dependent on the ability to detect the invasive mammalian predator and to then respond rapidly to remove all individuals. Without systematic monitoring it is highly likely that rats could arrive on an island (either by natural or human-assisted pathways) and remain undetected and then multiply quickly. Additionally, the features of the island such as its topography, harbourage, and its sources (or lack) of alternative food will play a role in this.

Assessing the actual risk

This part of the risk assessment considered the effectiveness of current biosecurity measures in reducing the potential risk of invasion and estimated the actual risk from invasive mammalian predators. It was carried out for all SPAs, those already invaded by mammals, and those which are still invader free. Current biosecurity measures were assessed against standards set in the UK Rodent Eradication Best Practice Toolkit (Thomas and others, 2017). They were scored as ‘sufficient,’ ‘below standard’ or ‘none’. At some sites, a biosecurity plan was in place, but the actual implementation of the plan had not yet taken place. In such cases, the assessment was based on the contents of the plan and on the assumption that it would be implemented.

Firstly, using data on actual biosecurity measures (for example, the prevention measures) in place at each site, the potential likelihood of incursions by rats and by mink was adapted (as low, medium or high) to reflect the ‘actual likelihood of incursion’ under those biosecurity measures. For example, if prevention measures were ‘sufficient,’ the actual likelihood of incursion would be assessed as lower than the potential likelihood. There would be no reduction in actual likelihood if there were no measures in place. To meet the standard of sufficient prevention measures, as many barriers and checks as possible need to be in place along pathways of introduction (Thomas and others, 2017). ‘Barriers’ usually involve placing traps or rodenticide stations at strategic locations that would:

-

prevent species getting on to vessels, either directly, for example, by climbing up mooring ropes or indirectly, for example, as a stowaway in cargo

-

prevent species dispersing from land within swimming distance of the island

-

identify the presence of species on vessels in transit

-

prevent species getting off vessels

-

prevent species getting out of quarantine areas on the island

Secondly, the potential risk from invasion was reassessed at each site given the measures in place that could reduce the likelihood of the invasive mammalian predator becoming established on the island. The first of these measures include an effective surveillance scheme designed to detect the incursion of an invasive species as soon as possible after it has occurred (for example, by using non-toxic wax blocks set inside bait stations, tracking tunnels, rodent motels, and trail cameras).

An example of a surveillance station on an island to monitor for potential rat incursions. (Photo credit: Sarah Lawrence)

An example of a surveillance station on an island to monitor for potential rat incursions. (Photo credit: Sarah Lawrence)

Once an invasive predator has been detected on an island, a rapid response is required to remove all individuals from the island before they spread far from the incursion point. Preparedness for incursion response was assessed through interviews with site managers. The biosecurity plans currently in development contain enhanced surveillance and incursion response plans to deal with possible, probable, or definite invasive predator sightings. For probable or definite rat incursion, response plans are based on setting up a grid of bait stations with rodenticide bait 50 m apart for 500 m in all directions around the sighting or sightings (100 ha, 441 stations) augmented with snap traps and non-toxic monitoring.

The combined assessment of surveillance and rapid incursion response measures was used to determine if the actual likelihood of invasion could be scored lower than the potential likelihood.

Finally, the lowest of the scores for likely impact and actual likelihood of invasion was entered as the vulnerability score into the risk matrix (Table 2), together with the actual likelihood of incursion score, to determine the overall actual risk from invasive mammalian predators at the site.

Results

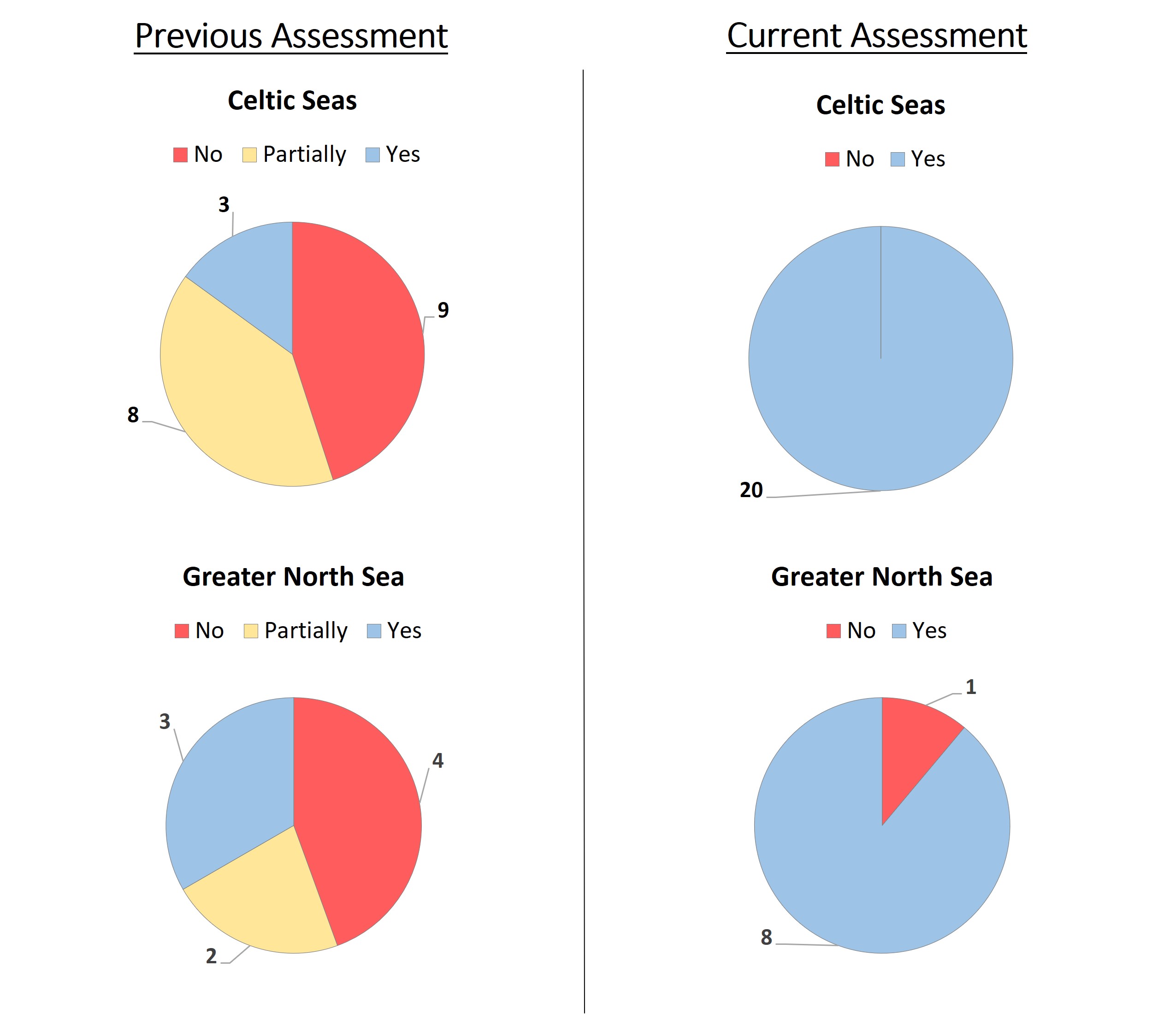

Findings from previous assessments

This indicator was not considered as part of the 2012 Initial Assessment (DEFRA, 2019a). For the assessment of 2018, no evaluation against the target of a reduction in risk took place as there were no previous data available for comparison. Therefore, the 2018 assessment was an initial stock take of the situation at the time. From this, it found that only 6 out of 42 island SPAs assessed had adequate biosecurity in place to reduce risk from invasive mammalian predators, and 13 had only partially minimised risk. The remaining 21 island SPAs assessed had no, or inadequate, biosecurity in place to reduce risk.

Latest findings

Status assessment

The target of risk reduction from invasive mammalian predators in island seabird colonies has been met as risks were reduced compared to the previous assessment. Of the 42 assessed island SPAs, 34 have improved in how well the risk was minimised and 8 remained the same since the last assessment. Forty of the island SPAs now have biosecurity plans in place, minimising the risk of invasion from mammalian predators. This is an improvement from the 6 that had reduced the risk and 13 that had only partially minimised the risk in the previous assessment.

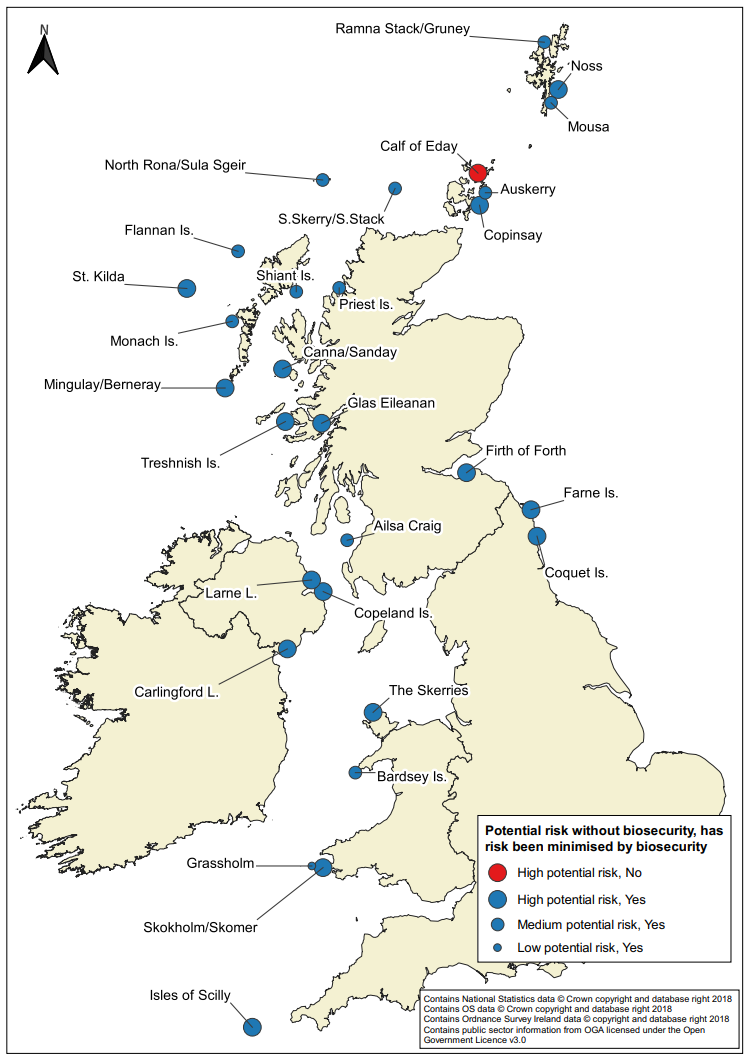

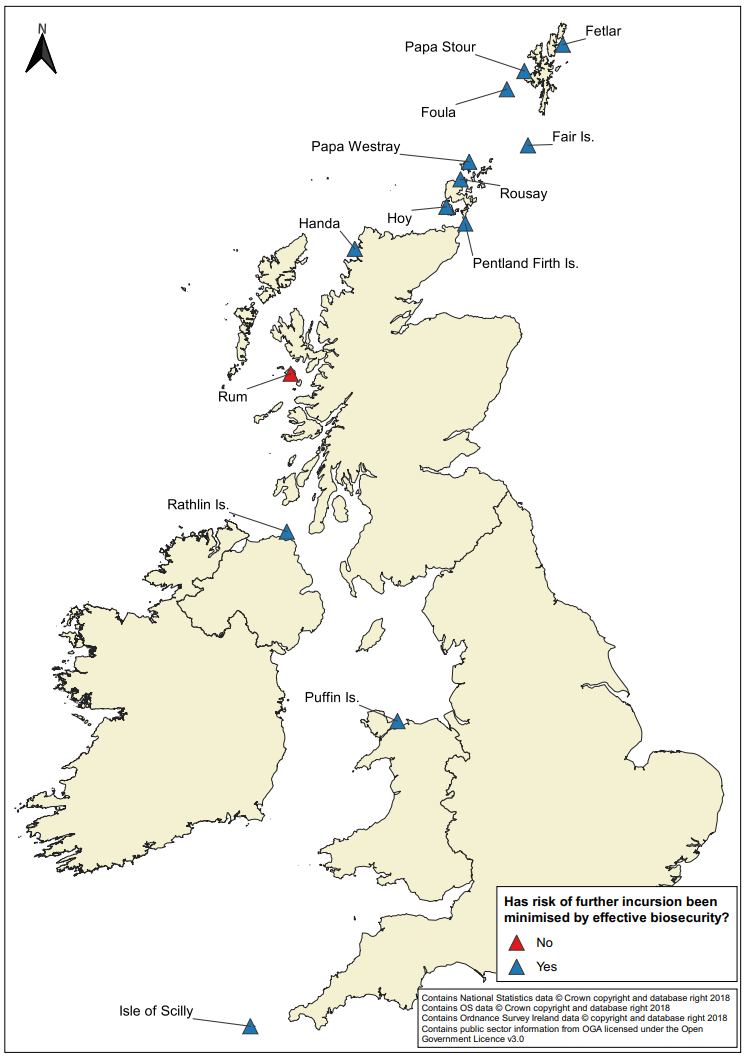

Twenty eight out of the 29 seabird islands that do not have invasive mammals present have effective biosecurity in place to sufficiently reduce the risk from invasive mammalian predators (Figure 2). Unfortunately, the number of seabird island SPAs with confirmed, or suspected, invasive mammalian predators present, has increased by one to a total of 13 SPAs since the last assessment. However, of these 13, only one SPA does not have effective biosecurity to sufficiently reduce the risk of further incursion (Figure 3). Additionally, at least two of these islands have plans to try and eradicate the invasive mammalian predators present, Rathlin Island and Puffin Island.

Figure 2: Current assessment results on whether the risk from invasive mammalian predators has been reduced on seabird island SPAs that do not have invasive mammal predators already present.

Figure 2: Current assessment results on whether the risk from invasive mammalian predators has been reduced on seabird island SPAs that do not have invasive mammal predators already present.

Figure 3: Island seabird colonies within UK Special Protection Areas (SPA), where invasive mammalian predators were present and the risk of further incursion has been minimised by biosecurity.

Figure 3: Island seabird colonies within UK Special Protection Areas (SPA), where invasive mammalian predators were present and the risk of further incursion has been minimised by biosecurity.

The biosecurity plans that are in place for 40 island SPAs were produced based on the UK Rodent Eradication Best Practice Toolkit (Thomas and others, 2017) and are therefore assumed to be sufficient in their minimisation of invasion from invasive mammalian predators. However, further in-depth research into pathways and legal responsibilities in terms of enforcement of stricter, or gold standard, biosecurity measures (such as those adopted in countries like New Zealand) should still be considered to improve the current programme.

Further information

Table 3 and Figure 4 show the summarised results of the step-by-step process to assess risk from invasive brown rats and American mink on the 29 island SPAs where both species are currently absent for both assessments. The column headings in Table 3, correspond to the steps outlined in the risk assessment process in Figure 1. Potential risk (without current biosecurity) and actual risk (with current biosecurity) were estimated using the risk matrix in Table 2, with the final column assessing if risk has been sufficiently reduced. The majority of the scores in Table 3 for the previous assessment were taken from interviews of site managers conducted by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) as part of the LIFE13 NAT/UK/000209 Shiant Isles Seabird Recovery Project (Thomas and others, 2016). The scores for the current assessment were largely based on the biosecurity plans in place, which are centred on the best practice outlined in the UK Rodent Eradication Best Practice Toolkit (Thomas and others, 2017).

Table 3: Summarised results from both assessments of the risk of invasive non-native rats and American mink and the effectiveness of biosecurity measures at island seabird colonies within UK Special Protection Areas (SPA) where they are not currently present.

a) Celtic Seas

|

Country |

SPA name |

Potential Risk (without biosecurity) |

Previous Assessment |

Current Assessment |

||

|

Actual Risk (with previous biosecurity) |

Has risk been minimised by biosecurity |

Actual Risk (with current biosecurity) |

Has risk been minimised by biosecurity |

|||

|

England |

Isles of Scilly1 |

High |

Low |

Yes |

Low |

Yes |

|

Northern Ireland |

Carlingford Lough |

High |

High |

No |

Low |

Yes |

|

Northern Ireland |

Copeland Islands |

High |

Medium |

No |

Low |

Yes |

|

Northern Ireland |

Larne Lough |

High |

High |

No |

Low |

Yes |

|

Scotland |

Ailsa Craig2 |

Medium |

Medium |

Partially |

Low |

Yes |

|

Scotland |

Canna and Sanday3 |

High |

Medium |

Partially |

Low |

Yes |

|

Scotland |

Flannan Isles |

Medium |

Medium |

No |

Low |

Yes |

|

Scotland |

Glas Eileanan |

High |

Medium |

Partially |

Low |

Yes |

|

Scotland |

Mingulay and Berneray |

High |

High |

No |

Low |

Yes |

|

Scotland |

North Rona and Sula Sgeir |

Medium |

Medium |

No |

Low |

Yes |

|

Scotland |

Priest Island |

Medium |

Low |

Yes |

Low |

Yes |

|

Scotland |

St Kilda |

High |

Medium |

Partially |

Low |

Yes |

|

Scotland |

Sule Skerry & Sule Stack |

Medium |

Medium |

No |

Low |

Yes |

|

Scotland |

The Monach Isles |

Medium |

Medium |

No |

Low |

Yes |

|

Scotland |

The Shiant Isles4 |

Medium |

Low |

Yes |

Low |

Yes |

|

Scotland |

Treshnish Isles |

High |

High |

No |

Low |

Yes |

|

Wales |

Bardsey Island/Ynys Enlli (part of Glannau Aberdaron & Ynys Enlli / Aberdaron Coast & Bardsey Island SPA) |

Medium |

Low |

Partially |

Low |

Yes |

|

Wales |

Grassholm |

Low |

Low |

Partially |

Low |

Yes |

|

Wales |

Skokholm and Skomer |

High |

Medium |

Partially |

Low |

Yes |

|

Wales |

The Skerries (part of Ynys Feurig, Cemlyn Bay and The Skerries SPA) |

High |

Medium |

Partially |

Low |

Yes |

1Isles of Scilly – refers only to Annet (successful response to rat incursion in 2004) and St Agnes and Gugh, where rats were eradicated in 2013/14 .

2Ailsa Craig – rat eradication in 1991.

3Canna & Sanday - rat eradication in 2005.

4The Shiant Isles – rat eradication in 2015/16

b) Greater North Sea

|

Country |

SPA name |

Potential Risk (without biosecurity) |

Previous Assessment |

Current Assessment |

||

|

Actual Risk (with previous biosecurity) |

Has risk been minimised by biosecurity |

Actual Risk (with current biosecurity) |

Has risk been minimised by biosecurity |

|||

|

England |

Farne Islands |

High |

Low |

Yes |

Low |

Yes |

|

Scotland |

Auskerry |

Medium |

Medium |

No |

Low |

Yes |

|

Scotland |

Calf of Eday |

High |

High |

No |

High |

No |

|

Scotland |

Copinsay |

High |

Low |

Yes |

Low |

Yes |

|

Scotland |

Firth of Forth5 |

High |

Medium |

Partially |

Low |

Yes |

|

Scotland |

Mousa |

Medium |

Medium |

Partially |

Low |

Yes |

|

Scotland |

Noss |

High |

High |

No |

Low |

Yes |

|

Scotland |

Ramna Stacks & Gruney |

Medium |

Medium |

No |

Low |

Yes |

5Firth of Forth Islands – includes Isle of May, Bass Rock, Inchmickery, Craigleith, Lamb and Fidra. All are rat-free.

Figure 4. The number of UK Special Protection Areas where invasive predatory mammals were absent in each assessment and where biosecurity measures have minimised the risk (yes, partially or no) from invasive predatory mammals arriving and becoming established. Please note one of the Celtic Seas sites has had a rat incursion since the previous assessment, therefore totals across the assessments for this region do not match.

Rats have been eradicated from some of the islands included in Table 3 – a review of these eradication programmes is provided in Stanbury and others (2017) and Ratcliffe and others (2009). These included a long running eradication programme on the Isles of Scilly. In 2013, the islands of St Agnes and Gugh were declared rat-free (http://www.ios-seabirds.org.uk), but work is ongoing to prevent reincursions of rats at other islands in the archipelago. Most recently, in 2015, work began to eradicate black rats from the Shiants Islands in Western Isles. In 2018, the Shiant Isles were declared rat-free after intensive monitoring recorded no signs of rats for two years, the internationally agreed criterion for rat-free status. There have also been schemes to eradicate and control the spread of American mink – on Lewis and Harris in the Western Isles (Hebridean Mink Project | NatureScot) and in and around the sea lochs of Argyll and Lochaber (Craik 1997, 1998).Conclusions

The UK target of a reduction in the risks to island seabird colonies from invasive mammalian predators was met (i.e. the risk was reduced compared to the previous assessment). However, there are still island SPAs where no measures are in place and the risks from invasive mammalian predators need to be further minimised. The success of this indicator has hinged on the hard work put in by the Biosecurity for LIFE project. The establishment of a UK wide, sustained biosecurity programme will be essential in maintaining this indicator’s positive outcome.

This assessment included invasive native species of predatory mammals as well as non-natives. It focussed on all the 42 SPAs that were designated to protect the UK’s most important seabird colonies on offshore islands. These sites receive the highest level of statutory protection. Despite this, invasive predatory mammals (brown rats, domestic and feral cats, and hedgehog) are present at 13 SPAs.

Brown rats and other invasive predatory mammals are present at 13 SPAs. This camera trap photo shows a rat captured using remote monitoring technique of camera trapping. (Photo credit: Justin Hart)

Brown rats and other invasive predatory mammals are present at 13 SPAs. This camera trap photo shows a rat captured using remote monitoring technique of camera trapping. (Photo credit: Justin Hart)

The risk from high-risk invasive mammalian predators has been minimised by effective biosecurity at 28 of 29 island SPAs where invasive predators are absent (including Isles of Scilly SPA). The only invasive predator-free site without biosecurity is the Calf of Eday SPA in Scotland.

This assessment was conducted with moderate confidence: confidence in data availability was high, but the methods used in this risk assessment have now been used only for two consecutive assessments.

Further information

Future assessments of this indicator must ensure at the very least the continuation, if not the improvement, of biosecurity on our seabird island SPAs. This should include awareness raising, prevention measures (such as barriers on pathways and engagement of key stakeholders through schemes such as the “predator free warrant”), on-island surveillance, and incursion response. Even though the indicator is improving, the progress is hinged on the success and hard work of the Biosecurity for LIFE project. Ensuring the legacy of this project continues will keep this indicator from declining back to its original state during the previous assessment.

The two SPAs that require improvements in biosecurity are in Scotland. One of these sites, Rum SPA, is inhabited and has an existing population of brown rats thus making the implementation of biosecurity a little more difficult, though not impossible given the success of biosecurity action seen in the Isles of Scilly. Increasing our understanding of pathways for invasive mammalian predators for each of the islands can ensure efficiencies are made in the prevention measures (barriers) and surveillance plans at each location.

In Northern Ireland, current biosecurity was assessed as sufficient at all four island SPAs. The single invaded island SPA, Rathlin, has recently received LIFE funding for a restoration project (LIFE RAFT, Rathlin Acting for Tomorrow) which will look to eradicate the invasive brown rats and ferrets that are present there. Ensuring there is continued funding support for the biosecurity already in place at the island, will enable continued protection post restoration action.

In England, all seabird island SPAs were deemed to have sufficient biosecurity in place to minimise risk of invasion, or re-incursion, of invasive mammalian predators. As with other countries, ensuring support for the continued implementation of biosecurity will safeguard the positive safety status of these islands in future assessments.

In Wales, evidence of brown rats was found on Puffin Island, however the other four SPAs are free of invasive mammalian predators. Although not all biosecurity measures were in place by the time of the incursion, some prevention was in place (based on the previous assessment) on Puffin Island, detection of the incursion was swift, and plans are in place for eradication to take place.

Knowledge gaps

This assessment identifies where biosecurity needs to be improved to meet the UK target in the future. Risk of further incursion has been reduced on 12 of the 13 SPAs where invasive predatory mammals are already present (Figure 2). However, little is known on what level of impact these invasive predators have had on the seabird populations breeding there. A better understanding of the extent of the impacts on seabirds and other ground-nesting birds in these SPAs will identify the measures needed to reduce these impacts.

Further information

It will not be easy to fully understand the impacts on seabirds at SPAs where invasive predatory mammals, particularly rats, are already present (Figure 1). If rats have been present for many years, a stable state of coexistence may have seemingly been established, so that impacts are not that visible. To elaborate, impacts of the rats may have occurred in the past when seabird distribution and abundance was unrecorded, so any long-term impact of rat presence remain unknown. Following the invasion by rats, breeding seabird distribution may have become restricted to areas that are inaccessible to rats, while some species, such as European storm-petrels, will have deserted the islands completely. There is unlikely to be any visible evidence of rat predation such as predated eggs or chicks on these islands, yet the impacts of rats persist.

Rats are absent from four SPAs where feral cats are present: Foula, Fetlar, Fair Isle, and Papa Stour. Predation by cats is usually more obvious than the impacts of rats including through the presence of predated bird carcasses. However, the extent of impacts by cats on these four SPAs is currently unknown,

References

Birkhead, T., Furness, R.W., 1985. Regulation of seabird populations. In: Sibly, R.M., Smith, R.H. (eds.). Behavioural ecology: ecological consequences of adaptive behaviour. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford, UK, 145–167.

Courchamp, F., Chapuis, J.-L., Pascal, M., 2003. Mammal invaders on islands: impact, control and control impact. Biological Reviews, 78(3), 347–383.

Craik, C., 1997. Long-term effects of North American mink Mustela Vison on seabirds in Western Scotland. Bird Study, 44(3), 303–309.

Craik, J.C.A., 1998. Recent mink-related declines of gulls and terns in West Scotland and the beneficial effects of mink control. Argyll Bird Report, 14, 98–110.

DEFRA, 2019a. Marine strategy part one: UK updated assessment and good environmental status. Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/marine-strategy-part-one-uk-updated-assessment-and-good-environmental-status (Accessed 25 May 2023).

DEFRA, 2019b. Marine strategy part three: UK programme of measures. Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/486623/marine-strategy-part3-programme-of-measures.pdf (Accessed: 25 May 2023).

Dunstone, N., 1993. The Mink. T. & A.D. Poyser, London, UK, 232 pp.

European Commission, 2009. Directive 2009/147/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 November 2009 on the conservation of wild birds (codified version). Official Journal of the European Union, L20(53), 7–25. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32009L0147 (Accessed 13 12 2023).

Ewins, P.J., Tasker, M.L., 1985. The breeding distribution of black guillemots Cepphus grylle in Orkney and Shetland, 1982–84. Bird Study, 32(3), 186–193.

Fraser, E.J., Lambin, X., McDonald, R.A. & Redpath, S.M. 2015. Stoat (Mustela erminea) on the Orkney Islands – assessing risks to native species. Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No. 871. https://www.nature.scot/doc/naturescot-commissioned-report-871-stoat-mustela-erminea-orkney-islands-assessing-risks-native (Accessed 13 May 2025).

GB Non-Native Species Secretariat, 2022. Brown rat Rattus norvegicus [Online]. GB Non-Native Species Secretariat. Available at: https://www.nonnativespecies.org/non-native-species/information-portal/view/2979 (Accessed 28 June 2023).

Jones, H.P., Tershy, B.R., Zavaleta, E.S., Croll, D.A., Keitt, B.S., Finkelstein, M.E., Howald, G.R., 2008. Severity of the effects of invasive rats on seabirds: a global review. Conservation Biology, 22(1), 16–26.

Lock, J., 2006. Eradication of brown rats Rattus norvegicus and black rats Rattus rattus to restore breeding seabird populations on Lundy Island, Devon, England. Conservation Evidence, 3, 111–113.

Mitchell, P.I., Newton, S.F., Ratcliffe, N., Dunn, T.E. (eds.), 2004. Seabird populations of Britain and Ireland: results of the Seabird 2000 census (1998-2002). T. & A.D. Poyser, London, 508 pp.

Mitchell, P.I., Ratcliffe, N., 2007. Abundance and distribution of seabirds on UK Islands – the impact of invasive mammals. In: Proceedings of the Conference on Tackling the Problem of Invasive Alien Mammals on Seabird Colonies–Strategic Approaches and Practical Experience. The National Trust for Scotland, Royal Zoological Society of Scotland and Central Science Laboratory, Edinburgh, UK.

National Biodiversity Network (NBN) Trust, 2023. NBN Atlas [Online]. Available at: https://nbnatlas.org/ (Accessed 28 June 2023).

Ratcliffe, N., Mitchell, I., Varnham, K., Verboven, N., Higson, P., 2009. How to prioritize rat management for the benefit of petrels: a case study of the UK, Channel Islands and Isle of Man. Ibis, 151(4), 699–708.

Russell, J.C., Clout, M., 2005. Rodent incursions on New Zealand islands. In: Parkes, J., Statham, M., Edwards, G. (eds.). Proceedings of the 13th Australasian Vertebrate Pest Conference. Landcare Research, Lincoln, New Zealand, 324–330. Available at: https://www.stat.auckland.ac.nz/~jrussell/files/papers/RussellClout2005.pdf (Accessed 13 12 2023).

Stanbury, A., Thomas, S., Aegerter, J., Brown, A., Bullock, D., Eaton, M., Lock, L., Luxmoore, R., Roy, S., Whitaker, S., Oppel, S., 2017. Prioritising islands in the United Kingdom and Crown Dependencies for the eradication of invasive alien vertebrates and rodent biosecurity. European Journal of Wildlife Research, 63, 31.

Thomas, S., Bambini, L., Vanham, K., 2016. Review of biosecurity on seabird SPAs in the UK. Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. Technical Report LIFE13 NAT/UK/000209 Shiants Project.

Thomas, S., Varnham, K., Havery, S., 2017. UK rodent eradication best practice toolkit (Version 4.0) [Online]. Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, Sandy, Bedfordshire, UK. Available from: https://www.nonnativespecies.org/non-native-species/management-guidance/hydrocotyle-ranunculoides-floating-pennywort/#UKrodentredication (Accessed 13 12 2023).

Towns, D.R., Atkinson, I.A.E., Daugherty, C.H., 2006. Have the harmful effects of introduced rats on islands been exaggerated? Biological Invasions, 8, 863–891.

Authors

Lead authors: Daisy Burnell1, Kerstin Kober1

Supporting Authors: Matthew Murphy 2, Sarah Lawrence 3, Richard Berridge 4, Justin Hart 4, Claire Macnamara 5.

1Joint Nature Conservation Committee

2 Natural Resources Wales

3 NatureScot

4 Natural England

5 Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs

Supported by: The Marine Bird Sub-Group of the Healthy Biologically Diverse Seas Evidence Group

Assessment metadata

| Assessment Type | UK Marine Strategy Assessment Part 1 (2025) – Indicator Assessment |

|---|---|

Marine Birds | |

| Point of contact email | marinestrategy@defra.gov.uk |

| Metadata date | Thursday, May 1, 2025 |

| Title | |

| Resource abstract | |

| Linkage | |

| Conditions applying to access and use | UK Government Data policy |

| Assessment Lineage | UK Marine Strategy Part 1 Assessment in 2019: |

| Dataset metadata | |

| Dataset DOI | Breeding data: Breeding birds Atlases of Britain and Ireland: https://www.bto.org/get-involved/volunteer/projects/completed/birdatlas-2007-2011/results/mapstore Gibbons, D.W., Reid, J.B., Chapman, R.A., 1993. The new atlas of breeding birds in Britain and Ireland: 1988-1991. T. & A.D. Poyser, London, UK. Balmer, D.E., Gillings, S., Caffrey, B.J., Swann, R.L., Downie, I.S., Fuller, R.J., 2013. Bird Atlas 2007-11: the breeding and wintering birds of Britain and Ireland. British Trust for Ornithology, Thetford, Analysis for this indicator was contracted to and prepared by the British Trust for Ornithology who own the Atlas datasets. Non-breeding data: Wetland Bird Survey (WeBS): https://www.bto.org/get-involved/volunteer/projects/wetland-bird-survey/data Non-Estuarine Waterbird Surveys (NEWS): https://www.bto.org/our-work/science/publications/reports/research-reports/results-third-non-estuarine-waterbird-survey-including Data for NEWS can be requested via the WeBS data request form. |

The Metadata are “data about the content, quality, condition, and other characteristics of data” (FGDC Content Standard for Digital Geospatial Metadata Workbook, Ver 2.0, May 1, 2000).

Metadata definitions

Assessment Lineage - description of data sets and method used to obtain the results of the assessment

Dataset – The datasets included in the assessment should be accessible, and reflect the exact copies or versions of the data used in the assessment. This means that if extracts from existing data were modified, filtered, or otherwise altered, then the modified data should be separately accessible, and described by metadata (acknowledging the originators of the raw data).

Dataset metadata – information on the data sources and characteristics of data sets used in the assessment (MEDIN and INSPIRE compliance).

Digital Object Identifier (DOI) – a persistent identifier to provide a link to a dataset (or other resource) on digital networks. Please note that persistent identifiers can be created/minted, even if a dataset is not directly available online.

Indicator assessment metadata – data and information about the content, quality, condition, and other characteristics of an indicator assessment.

MEDIN discovery metadata - a list of standardized information that accompanies a marine dataset and allows other people to find out what the dataset contains, where it was collected and how they can get hold of it.